Last week, we heard briefly about the beginning of Jesus’ ministry. After calling some disciples, Jesus travels around Galilee, teaching in synagogues, “proclaiming the good news of the kindom and curing every disease and every sickness among the people.” It’s no surprise that large crowds were following Jesus.

When he saw the crowds, here’s what Jesus did. He went up a mountain and sat down. The sitting down part was a signal that he was about to teach. His going up a mountain also was a sign the people would have recognized. Matthew is sometimes called “the Jewish Gospel.” That’s because it was written to a Jewish audience… which means the author used language and images that would connect with people of the Jewish faith.

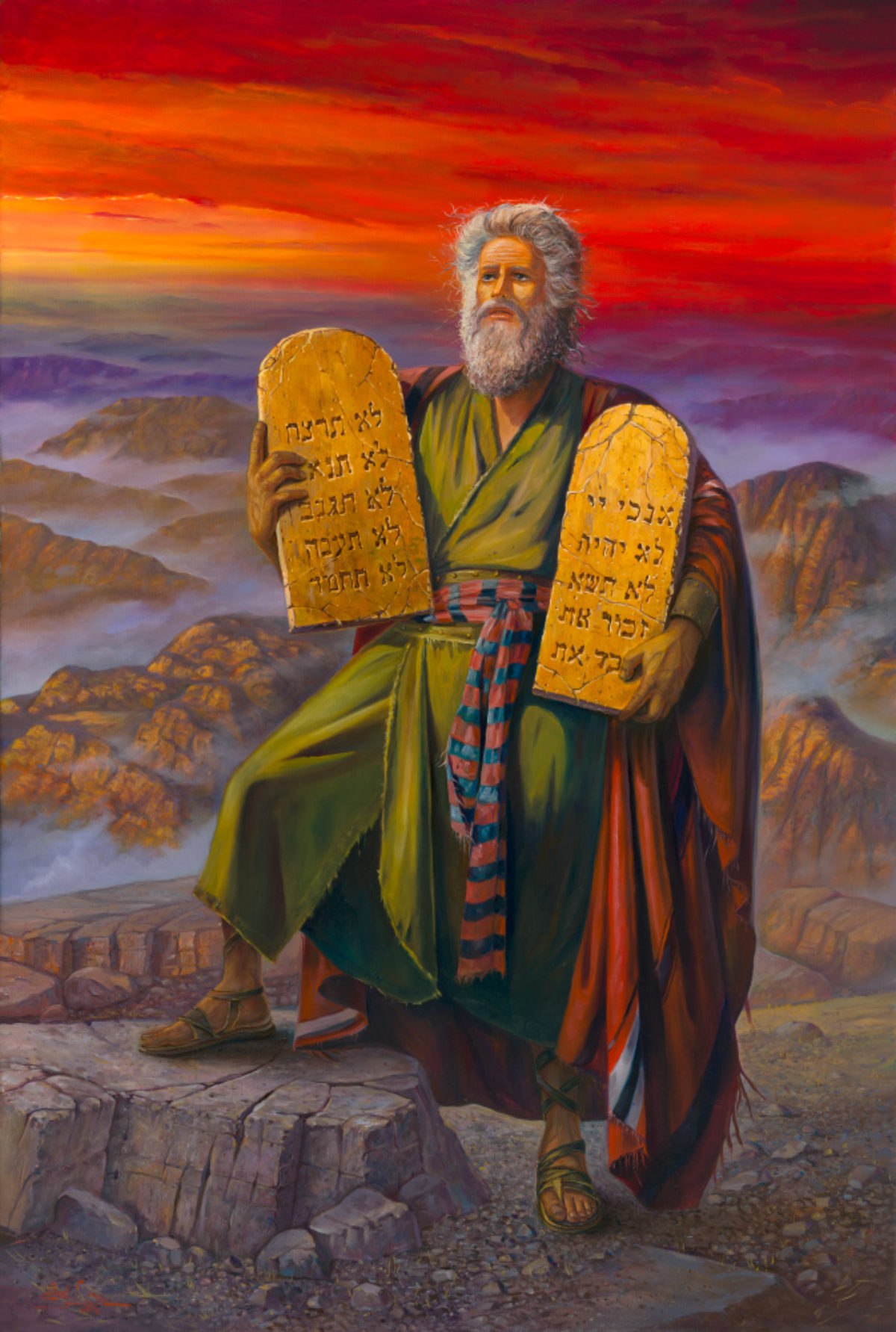

So, who in the Hebrew Bible went up a mountain to teach the people? Moses! And what happened when Moses went up the mountain? That’s when he gave the people the law–the Ten Commandments…with about a million footnotes, cf. the book of Leviticus.

So, when Jesus goes up the mountain and sits down, the Gospel writer is signaling that Jesus is bringing a new understanding of the law that had guided the Jewish people for centuries. “You have heard that it was said… But I say to you…” Jesus is a new Moses. While grounded in the tradition, Jesus’ aim was to reimagine their faith for the present time.

Which is what faith communities are all about, right? Our Judeo-Christian tradition is a rich one. We have the words of poets and prophets. We have Moses and Jesus, and Deborah and Dorcas. Much of what we do is grounded in that tradition.

AND…if our faith is to remain relevant, we have to constantly reimagine it for our time. If any times called us to reimagine our faith, these are them.

We’ve come to call Jesus’ teaching in Matthew 5 the Sermon on the Mount. Today, we hear the introduction to the sermon–the Beatitudes, or Blessings. Each beatitude is so densely packed, it would take a looooong time to deal all of them….so today, we’ll look at just one: “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

In the newsletter this week, I invited you to read through the Beatitudes and see how this Beatitude differs from the others. Did you come up with anything? (Responses)

In all the other Beatitudes, the ones referenced receive something. “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kindom of heaven.” “Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.” What do peacemakers receive? “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God.” It’s not, “they are, or will become children of God.” It’s “they will be called children of God.”

It’s true that creating peace is its own reward, but still. All the others receive something. The meek get the whole Earth! All the peacemakers get is a good standing in the eyes of others. I don’t mean to gripe, but why is everybody’s else’s gift so much better than ours?

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God.” They shall be called children of God. Here’s my first question. Who is it that will be calling peacemakers children of God? Other children of God? Religious authorities?

What if the folks who call peacemakers children of God, don’t themselves identify as God’s children? What if it’s people outside the community looking at the work of peacemakers and saying to themselves, “If there is a God, that’s what children of that God would be doing.”

People of faith–people of Christian faith–are called lots of things these days, aren’t we? “Children of God” isn’t high on the list of things we’re called. Truth be told, the church has earned its disparagement. Over the centuries, the church has done some horrific things…the Inquisition…the Crusades…the Magdalene laundries in Ireland…colonization in Africa, South America, and our own country…much of the systemic racism that defines our country was authored by people of Christian faith…and we haven’t even gotten to the church’s terrible treatment of LGBTQ people or covering up clergy sexual abuse…

Oh, yes. The church has earned the epithets it has received. All things considered, being called “children of God” might be nice. In fact, being called “children of God” by people outside the church might be a very good gift indeed, maybe almost as good as inheriting Earth.

So, how do we do that? How can we do and be church in a way that will lead folks outside the church to call us “children of God?”

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God.” If peacemakers are called children of God, then the thing people most associate with God-ness must be peace, wholeness, shalom. When people are able to live as whole, fully-authentic human beings, others see God. When Earth and all its creatures are able to thrive in good health, others see God. When communities and countries work for the common good, others see God. So, when we help people live whole lives, when we work for environmental wholeness, when we work for the common good, if this beatitude is right, then others will see us as God’s children.

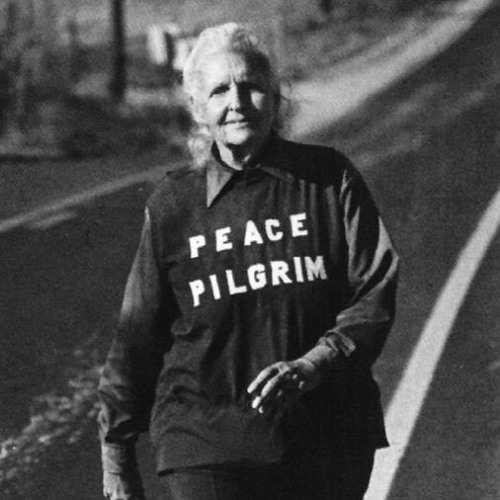

Peacemaking is a concept it’s hard to wrap your mind around. A lot of times, it’s taken narrowly to mean anti-war. Certainly, anti-war activism is a part of peacemaking, but peacemaking encompasses a whole lot more than anti-war activism. Peacemaking encompasses any activity that contributes to any created being living as it was created to live.

I saw an article this week that said suicide rates of folks who are LGBTQ are down dramatically since marriage equality was passed. Working for marriage equality was an act of peacemaking. Three weeks ago, this community celebrated the arrival in this country of Karina’s dad and Basem’s wife and daughter. Laws and advocates that made it possible for that to happen? Peace work. And, as Horace reminded us two weeks ago, so many more people are languishing at our borders. Writing new laws, opposing unjust laws, protesting against the indignities and trauma imposed on people waiting for their immigration cases to be heard–all of that is peace work.

We could spend all day–all week–listing off all the people and situations longing for peace. At the heart of any peace work in which we might engage is a core commitment: a commitment to honoring and working for the dignity of every single living thing.

May 27, 1992, soon after the siege of Sarajevo began, a bomb fell in one of the city’s squares. Twenty two people, standing in line to buy bread, were killed. A neighbor of those 22 people, Vedran Smailovich, played cello in Sarajevo’s symphony orchestra.

On May 28, Vedran appeared in the square dressed in his tuxedo, carrying his cello. He grabbed one of the up-turned chairs from a nearby restaurant, opened his case, and began to play. For the next 21 days–for a total of 22–Vedran Smailovich played the same piece…under threat of bombing or sniper attack, he played each day, once for each life lost. With his tuxedo, with his playing, by creating beauty in the center of a bomb crater, Smailovich sought to remember—literally, to re-member–the dignity of lives so senselessly lost.

The story is told that during one of his mini-concerts, a soldier asked Smailovich, “Why are you playing where there is bombing?” A bewildered Smailovich replied, “Why are you bombing where I am playing?”

It’s a simple exchange that goes to the heart of peacemaking: reframing everything, everything, in terms of peace. From the soldier’s perspective, a cellist playing in the middle of bomb crater was absurd. In the soldier’s mind, all around them was a war zone. In Smailovich’s mind, it wasn’t his playing that was absurd, but the war. Before the siege began, Sarajevo was a place where Jews, Christians, and Muslims got along very well, a place alive with the arts, a city that, just 8 years before, had hosted the Winter Olympics. A cellist playing in the streets of Sarajevo wasn’t the absurd thing. The thing that was absurd was dropping a bomb on people who were in line to buy bread.

Each of us makes peace in our own way. Some of us march for peace. Some of us feed the hungry or visit the imprisoned. Some of us work for structural change by working for political candidates and for more just legislation. Some of us work for peace by praying or tending to our own internal peace.

Whatever the venue or peacemaking tasks in which we engage, the heart of it all begins where the cellist of Sarajevo began: by reframing every venue, every task in terms of peace. Creating beauty in the midst of war is not absurd. Creating war in the midst of beauty—that is what’s absurd.

The piece Smailovich played those 22 days is a haunting melody attributed to Tomaso Albinoni, an 18th century composer. There’s actually some debate about exactly who wrote it. One story has musicologist Remo Giazotto finding a scrap of a composition by Albiononi in the rubble of Dresden after it was bombed in World War II. Giazotto based the piece we now know as Albinoni’s Adagio in G on the bass line written on that scrap of paper from Dresden.

Whoever wrote it, it is a beautiful melody…and it became more beautiful when Vedran Smailovich played it to resurrect the dignity of 22 lives lost as they stood in line for bread. As Claire plays the Adagio—a tribute to one man’s fearless commitment to peacemaking—may it spark in each of us a renewed commitment to working for peace in our world. Claire?

(Claire plays “Adagio”)