Have you ever been lost? The first year at my last church, I pretty much stayed lost. Atlanta is not kind to the directionally-challenged.

Thanks to the little lady in my phone, I’m doing better–not perfect, but better–here in Asheville. Switchbacks and swift elevation changes do stymie her from time to time, but overall, I get where I need to go when I need to be there. Praise be to the little lady in my phone!

In Luke 15, Jesus tells three stories about the lost—the lost sheep, the lost coin, the lost child. The stories come late in Luke’s narrative. One wonders whether Jesus latched onto the metaphor of lost-ness because he, too, was directionally-challenged. Maybe…maybe…

Or maybe the idea of lost-ness emerges from the people he sees in front of him…people rejected by the religious establishment, like tax collectors and sinners…as well as representatives from that religious establishment, Pharisees and scribes.

Perhaps as Jesus looked over the crowd—the sinners raptly listening to his every word, the scribes grumbling—maybe when Jesus looked into the faces of those desperate and grumbling people, maybe he thought to himself, Lost. They seem so lost.

So, he tells three stories about the lost. In the first, one sheep from a flock of 100 gets lost. The shepherd secures the 99, then searches for and finds the lost sheep. Jesus says: “There will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over 99 righteous people who need no repentance.”

Next, Jesus tells the story of the poor widow’s lost coin. She tears up the house looking for it. When she finds it, she throws a party, so happy is she to have found what was lost.

It seems pretty clear where Jesus is headed with these stories. He’s reminding both the so-called “lost ones” (the sinners and tax collectors) and the righteous people (the Pharisees and scribes) that God loves the lost…that no matter where they’ve gone or who they are or what they’ve done, they are included in God’s kindom.

Good stories. Great message: welcome everyone because God welcomes them. Terrific!

But Jesus isn’t done yet. He has yet one more story to tell—the story of the lost child.

A man has two sons. The younger asks for his inheritance so he can go make his way in the world. The elder brother hears the exchange and mutters, “Of course you do.” The younger brother goes out into the world…and parties heartily, parties every bit of his inheritance away.

With no money–no nothing–he is truly lost. When he finds himself again—in a pen, slopping hogs and wishing for some of that slop for his own supper—this thought comes to him: “If I were a servant in my parent’s house, I’d be eating much better than this. I’d have clothes, a meaningful job… Let me go back to my father’s house.” And so, he goes.

Can you imagine? Coming home after squandering your inheritance, after living a life of debauchery, after losing absolutely everything…can you imagine coming home after that? The prodigal must have been terrified.

But he needn’t have been, because his father, seeing him in the distance, runs to meet him and embraces his son who’d been lost but now is found. Then the father calls for a BIG party to celebrate the return of son who’d been lost…

This is where the third story of the lost takes an unexpected turn. Now the spotlight turns to the older brother, the one who’d been at home all along. When the father announces the party, in resentment the older son says, “For all these years I’ve been working like a slave for you, and I’ve never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!”

Ah. So now we know that it’s not just the younger son who’s been lost. The son who stayed home was lost, too. It’s not just the tax collectors and sinners who are lost. The Pharisees and scribes are lost, too.

We’re all lost, aren’t we? We all want to feel loved, to feel at home, to feel special. Sometimes, like the Pharisees and scribes, we get the idea that it’s our status or our proximity to holy things or holy people that makes us special. What we learn in this final parable of the lost is that it isn’t our status or anything we’ve done that makes us special. What makes every person special is God’s unconditional love. When we realize that we’re all lost, that we’re all desperate for home, that we all just want to feel loved…when we realize that all of us together are trying to find our way home…That is when we begin to get a glimpse of God’s kindom.

Several of us drove to the Swannanoa Corrections Center on Wednesday to hold a prayer vigil. Sitting on the lawn by the entrance, peering through the chain link fence… It looked like young women walking between classes on a college campus. It felt like we were the ones on the outside looking in, like the chain link fence wasn’t there to keep them in, but to keep us out.

That’s when it hit me–we’re all the same. We all want to be loved. We all want to be connected. We all do beautiful things. And we all mess up. Learning what we have in the Just Mercy class about the stunning inequities in the criminal justice system, what puts some people in prison and keeps others out isn’t so much that the people inside are bad and the people outside good…the system is more arbitrary than that. Looking through that chain link fence, I realized that we’re all the same. As I watched a young woman working in a greenhouse, I meditated on Bryan Stevenson’s observation that none of us is as bad as the worst thing we’ve ever done. That gardener–she isn’t defined by whatever she did to put her in prison.

It’s like Chaplain Dalton said at the choir concert here in this room Friday night. Present were four women who’d served time in the Swannanoa Corrections Center….but none of us knew who they were….because, we’re all the same.

Joyce Rupp captured our sameness in a poem called Prisoners.

They walk in with their tan uniforms,

while the five of us “visitors”

walk in with our identity badges.

I look around the group

and think to myself:

“If we left our badges and uniforms

outside the door,

no one would ever know who is who.”

Ethnic heritage, life situations,

personality patterns, clouded dreams,

choices and decisions made wrongly,

who can say just what it was

that brought these women here.

I feel compassion in a new way,

one among them, not apart,

at home with them,

and unafraid,

knowing them to be my sisters,

not just “prisoners of the state.”

We’re all the same. We’re all beautiful. We’re all broken. We all do good things. We all mess up. We’re all lost and long to be found. And we’re all loved deeply, unconditionally, fiercely by God.

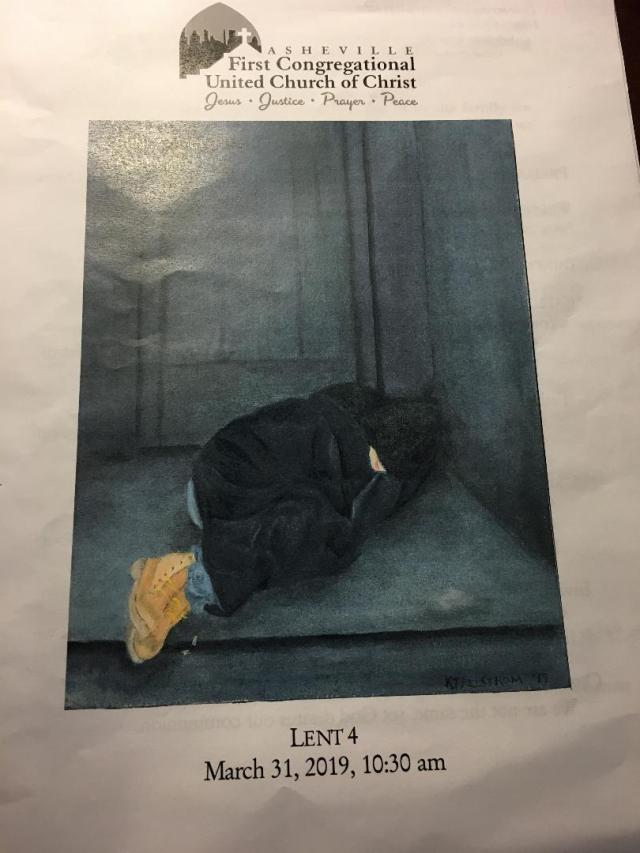

Today’s artwork was created by Mandy Kjellstrom. I asked Mandy to share the story behind the painting. Here’s what she wrote:

On a Sunday morning in February I walked to church taking the same route I always take and passed this doorway where the young man or older boy (impossible to tell) was sleeping. Frequently on Sunday mornings there is someone sleeping in this doorway on Broadway near the intersection with Woodfin in downtown Asheville. It always gives me pause to reflect on my life and the person’s sleeping in the doorway. After all, I am walking to church wearing nice clothes having slept in a warm house and comfortable bed and eaten a healthy breakfast. Usually the person in the doorway is poorly dressed and looking pretty uncomfortable and will most likely wake up very sore and very hungry. So I am smack dab in the middle of a tension of the opposites. And so are we all. How is it that in this country we can have these opposite extremes? What is the solution? We have to be creative in solving it and we have the capacity to solve it, right here, in our little city, if we put our minds and hearts into it.

But about this particular person in the doorway. As I said, I snapped the photo about 6 weeks ago, but I’ve kept going back and looking at it and thinking about this particular person. He has stayed on my mind and in my heart. And what comes to me so clearly is: This is someone’s child. He looks so young to me. What could his story possibly be? Does he have a mother who loves him and is worried sick about him? I hope so. Or does he have a mother who has hurt him deeply and from whom he’s running away? Does he even have a mother? Maybe he is just traveling. It is impossible to know. I have never seen him again in that doorway. But I do know, without his knowing it, he touched my life.

Sometimes creating a painting can be a very sacred time. Not always, just sometimes. Reflecting on this young man while painting him was one of those times.

In a subsequent email, Mandy shared the name of the painting: “Our Child.” Our child. That young man is our child…because we belong to each other. All of us are part of the same family. All of us are loved unconditionally by the creator of the universe.

I wonder how the world might change if we really believed that? I wonder how the world might change if we lived it?

In the name of our God, who creates us, redeems us, sustains us, and hopes for our wholeness. Amen.

Kimberleigh Buchanan © 2019

![The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness by [Wiesenthal, Simon]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/5161qNIeiLL.jpg)